A recent publication by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) attempts to address the question whether migration has a positive impact on the economy in host nations.

Migration takes many forms internationally. The populations of countries including Canada and Australia rely on managed migration to fill gaps in their labour markets and meet a number of demographic developments, especially in Canada, in part to offset low fertility rates, an aging population, a growing elderly dependency ratio, a shrinking labour force and high out-migration rates.

In contrast, migration within the European Union, features freedom of mobility between member states.

The impact of migration on societies is controversial, but is it economically beneficial? Do migrants add value to economies or are they a burden on the societies they join? In Canada, the answer recently became somewhat clearer following a recently published study providing conclusive evidence that immigrants admitted to Canada under all programs are far more likely to start businesses than their Canadian counterparts, a key component for economic growth. Released in March 2016 and entitled Immigration, Business Ownership and Employment in Canada, the study concludes that ‘rates of private business ownership and unincorporated self-employment are higher among immigrants than among the Canadian-born population’.

Then there is the generational impact of migration. How do you measure the value added to a country’s economy by an immigrant’s children, and their children further down the line? A recent Statistics Canada study highlighted that immigrant children outperform their Canadian counterparts in terms of both high school and university graduation rates. The study found 91.6 per cent of children who arrived in Canada between 1980 and 2000 graduated high school, against 88.8 per cent of their Canadian peers. In terms of university graduation, that gap widened to 35.9 per cent of immigrants versus 24.4 per cent of Canadians.

The OECD paper begins by establishing facts about migration under three headings: labour market, public purse and economic growth. Some important observations can be summarized as follows:

Labour markets

- Migrants accounted for 47% of the increase in the workforce in the United States and 70% in Europe over the past ten years.

- Migrants fill important niches both in fast-growing and declining sectors of the economy.

- Like the native-born, young migrants are better educated than those nearing retirement.

- Migrants contribute significantly to labour-market flexibility, notably in Europe.

Public purse

- Migrants contribute more in taxes and social contributions than they receive in benefits.

- Labour migrants have the most positive impact on the public purse.

- Employment is the single biggest determinant of migrants’ net fiscal contribution.

Economic growth

- Migration boosts the working-age population.

- Migrants arrive with skills and contribute to human capital development of receiving countries.

- Migrants also contribute to technological progress.

These facts fuel a debate on the importance of migration which in turn helps shape education and employment policies to maximize its benefit, especially where attracting migrants into the workforce is concerned. Few can argue that an unemployed migrant becomes a major financial and social drain on society.

For many countries with an aging population, immigrants are increasingly an important tool in filling labour force gaps and therefore it becomes important for individual countries to formulate policies geared to ensuring a positive impact for both the receiving country and the immigrants themselves.

During the past ten years, migrants accounted for 47 per cent of the workforce increase in the United States, and 70 per cent in Europe. Family, humanitarian and economic migration was the main sources with managed, labour force migration accounting for a relatively small part of the stream. Migration in these countries underscores the important contribution immigrants provide to their labour markets.

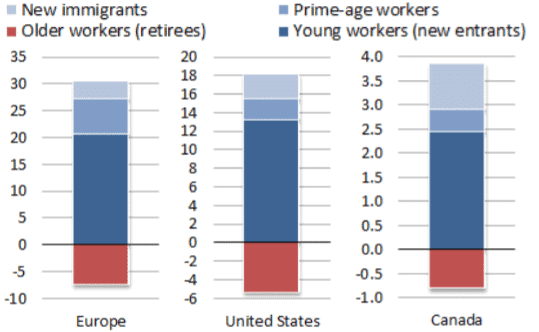

Changes in the tertiary-educated labour force, 2000-10 by source Millions

The level of migrant education, an important predictor of successful settlement, follows a similar pattern to the native-born population: the young are more educated than the old. Of migrants who find employment, more than a third have higher-education qualifications, but the same number never completed high school. Since 2000/01, immigrants have represented 31 per cent of the increase in the highly educated labour force in Canada, 21 per cent in the United States and 14 per cent in Europe.

Immigrants also fuel the most dynamic parts of the economy. Where an industry is growing, migrants will be playing a part and the same where an industry is declining, despite the majority of migration not being driven by workforce needs.

New immigrants represented 22 per cent of entries into strongly growing occupations in the United States and 15 per cent in Europe. Sectors include healthcare, science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Additionally, immigrants represented about a quarter of entries into the most strongly declining occupations in Europe (24 per cent) and the United States (28 per cent). In Europe, these occupations include craft and related trades workers as well as machine operators and assemblers; in the United States, they concern mostly jobs in production, installation, maintenance and repair. In all these areas, immigrants are filling labour needs by taking up jobs regarded by domestic workers as unattractive or lacking career prospects.

The growth of the EU has greatly increased the mobility of the labour market over the years, particularly following the EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007. This added to labour markets’ capacity to adjust quickly.

Looking at the economic benefit of migration, it appears to be questionable. A 2013 study titled ‘The Fiscal Impact of Immigration in OECD Countries’ provided internationally comparable evidence for the first time, and concluded that the better developed European countries, plus Australia, Canada and the US, put the impact close to zero, or at least within 0.5 per cent of GDP, whether positive or negative. The study looked at migration over the past 50 years.

The impact is highest in Switzerland and Luxembourg, where immigrants provide an estimated net benefit of about 2 per cent of GDP to the public purse.

While this appears to suggest migrants do not benefit the public purse, it also concludes they are not a burden.

In most countries, except in those with a large share of older migrants, migrants contribute more in taxes and social contributions than they receive in individual benefits. Therefore, migrants do contribute to public infrastructure projects, although not by as much as the native born.

Contrary to widespread public belief, low-educated immigrants contribute more than their native-born equivalents in terms of taxes paid versus benefits received. When consideration is factored that immigrants are often paid less for the same jobs, meaning they also contribute less is taxes, this factor is brought into clearer focus.

The age and categorization of migrants also has a major impact on whether they contribute or are a drain on the economies they move into. As one would expect, where seasonal labour migrants are the major component of immigrant population, they contribute more to the economy than humanitarian migrants. Labour migrants tend to have a much more favourable impact on the host country than other migrant groups.

Estimated net fiscal impact of immigrants, with and without the pension system and per-capita allocation of collectively accrued revenue and expenditure items

Employment is often the single most important determinant of a migrant’s economic contribution to a host country. If migrant employment is raised to the same level as native-born employment in many European countries, significant GDP gains would be realized. It could also help immigrants meet their own goals: Most immigrants do not relocate for social benefits, but to secure work and to improve their lives and those of their families through foreign remittances. Efforts to better integrate immigrants should thus be seen as an investment rather than a cost.

International migration has both direct and indirect effects on economic growth. There is little doubt that where migration expands the workforce, aggregate GDP can be expected to grow. However, the situation is less clear when it comes to per capita GDP growth.

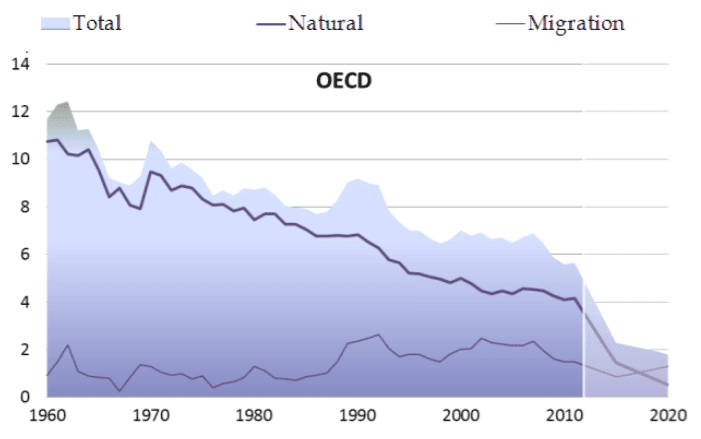

Components of total population growth in OECD countries, 1960-2020, per thousand inhabitants

Migration obviously increases population size, as well as the age balance towards a younger work force. With migrants often concentrated in the younger age groups, the structure of the receiving country’s population is positively impacted, often reducing age dependency ratios.

Migrants also arrive with skills and abilities, boosting human capital. A study entitled ‘Skilled Immigrants’ Contribution to Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the US’ suggests a positive contribution to research and innovation, occurs with an immigration inflow and therefore technical progress can be realized.

The movement of well-educated immigrants to developed countries is also on the increase, with figures showing a 70 per cent rise in the last decade, primarily driven by Asian migration. This seems to justify a growing movement towards study programs in host nations with the USA, UK, Australia and Canada leading the way. Canada is currently devising policies that will make it easier for international student graduates to remain permanently in Canada under its Express Entry system.

A lack of comparable data makes it difficult to estimate the overall impact of migration on economic growth. A study titled ‘Immigration and Economic Growth in the OECD Countries 1986-2006: A Panel Data Analysis’ that looks at the impact of migration on economic growth for 22 developed countries between 1986 and 2006 demonstrates a positive but fairly small impact.

An increase of 50 per cent in net migration generates less than one tenth of a percentage-point boost in productivity.

But when you consider rates of business ownership among immigrants, and the superior educational performance of immigrant children, as outlined in the two Canada-specific studies mentioned above, the economic benefits of migration begins to become clearer.

The OECD study seems to provide some compelling but very general observations. Individual country dynamics, especially in Canada, become more important factors in assessing the overall benefits of immigration which this study seems not to have addressed.

Click here to find out how we can help you find a job in Canada.

Interested employers: Kindly contact us here to receive further information.

Interested candidates: Find out whether you qualify to Canada by completing our free on-line evaluation. We will provide you with our evaluation within 1-2 business days.

Recent News Articles:

- International Student Post Graduate Work Program (PGWP) Creating Low-Wage Work Force

- Liberal spending plan to boost Canada’s economy, central bank predicts

- Helping new immigrants find jobs in Canada

Read more news about Canada Immigration by clicking here.